Fifteen minutes. That’s all we have at 500 feet. Hours of preparation, years of training, for just a quarter of an hour. All other fundamentals like buoyancy, propulsion techniques, team awareness and the nuances of your equipment have to be habitual. Each dive costs hundreds of dollars. Wasted seconds is wasted money. In every breath you take, millions of inert gas molecules rush into your tissues. This is decompression diving. Going to the surface is not an option. For if you do, you will die. Why do it then? We are the first human beings to see these reefs and often the first to see new species. It is the most euphoric and intense fifteen minutes imaginable.

Long before this dive, there was a little boy that looked up at an aquarium exhibit and something inspired him to become a marine biologist. Do you believe in love at first sight? Growing up at the Aquarium of the Pacific in Long Beach, California, the boy was mesmerized by the “Tropical Pacific,” a section of the aquarium that imitated Palau’s coral reefs. Fast forward to this past September. A gracious email invitation to attend an expedition with the California Academy of Sciences team to Palau. Missing this trip was not an option! The expedition was scheduled to begin December 6. The trip would occur well before finals. Meeting with farsighted and flexible professors, it was negotiated that exams would need to be taken early.

Palau is an incredible island country located 4,600 miles southwest of Honolulu. The mission for the expedition was to conduct biodiversity surveys and collect live specimens for the Steinhart Aquarium. This was a huge project consisting of three teams. Members of the “shallow” team (diving to 130 feet) were the invertebrate curators from Cal Academy based out of HQ, the Coral Reef Research Foundation. For us, the “deep” team, we occupied a significant portion of the facility at Sam’s Dive Tours, the largest diving operation in Palau. Lastly, there was a team of aquarists who had the responsibility of caring for all the live specimens that were collected. This team operated out of Biota, a local and sustainable aquaculture facility. The glue holding all of us together was Project Manager, Cristina Castillo, who was back-and-forth between the facilities ensuring everything was going smoothly.

The expedition began with the unpacking all of the cylinders, safety equipment, compressed gas, and rebreather consumables that were sent two months earlier. After organizing the equipment, it was time to assemble the rebreathers and blend gas; lots of gas. Since preparing a rebreather to dive is similar to preparing a plane to fly, checklists are a must. One of the perks to the project was getting to use very cool diving toys, I mean tools. One example was the $2,000 “NERD” (Near Eye Retinal Display), a full trimix closed circuit rebreather computer conveniently located on your heads up display! After an initial check out dive, it was time to get to work.

Each day started at 6:00am with breakfast at our hotel. It was the only time to get half-decent Wi-Fi as most of the other guests were still asleep. After coffee, scrambled eggs, and emails, we shuttled down to the dive center, departing at 7:45am. We stayed in the capital, Koror, where about 70% of the population of Palau lives. In our drives to the dive center, sometimes in the back of a truck, we were overwhelmed by the beautiful island country. On the way, we would stop at a local market to buy lunch for the day. It didn’t have a diverse menu. Milkfish, teriyaki chicken, and fried chicken were our options. Needless to say, some of us got tired of fried chicken by the fifth day in a row. Who knew a PB&J sandwich could be such a comfort food?

By the time we strategically arrived at Sam’s Tours at 8:15am, the morning boats had departed--leaving us room to operate. Typically, we spent about two to three hours preparing for the dive. This included assembling the rebreather, packing the CO2 scrubber, analyzing gasses, programming our gasses into the dive computers and getting all of the collection equipment aboard our chartered 40 foot boat. If we were going to be collecting fish, a chase boat followed us with our team of aquarists. The teams generally left the dock between 10:00am and 11:00am.

Once we made it to the day’s dive site, all personnel participated in an extremely detailed and thorough safety briefing. We reviewed the dive plan with every contingency imaginable. After we were in agreeance, it was time to suit up. Everyone was quiet as we mentally visualized the dive and conducted our individual pre-dive safety checks. With a 100 pound rebreather on our backs, and a cornucopia of safety equipment in our pockets, our safety diver led us through the team’s pre-jump checklist.

After we splashed into the water, it was time to receive our scooter, nets, fish decompression chambers, and all of our bailout cylinders from the crew. With everything clipped off, the team visually confirmed that everything was where it was supposed to be and that there were no visible leaks. Due to the complexity, it usually took over an hour from the time we geared up, to begin our dive.

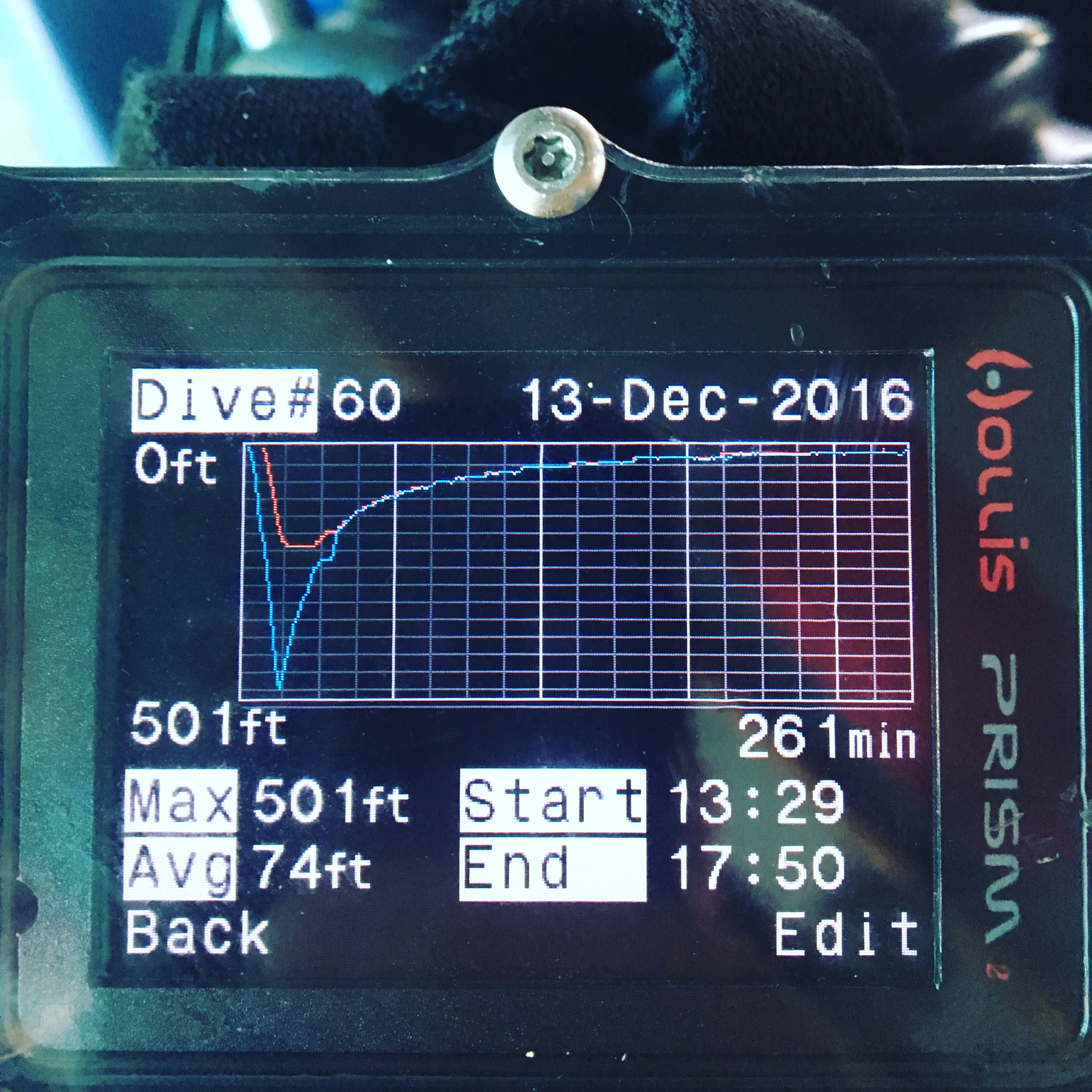

The team made eight mesophotic dives during the expedition with an average max depth of 360 feet and an average run time of four hours. Our planned depth and duration was mainly predicted by the dive site’s topography. Logistics definitely played a significant factor. If our site was further away, we tried to keep the dive shallower and shorter. The exception to this was the dive at Angaur Island, the southernmost island in Palau. We knew from talking to locals and looking at bathymetry maps that we would have the best chance of finding a desirable species of Centropyge. Everything was prepped the day before to leave the dock at 7:30am for the two hour boat ride out. Spending more time on the bottom also meant for greater decompression obligations. Remember how I said we only had fifteen minutes to work at 500 feet? At Angaur we worked for an incredible 40 minutes at 430 feet which resulted in 5.5 hours of decompression! It was our most productive dive. We collected a dozen beautiful specimens, including two undescribed fish species. The long decompression was worth it.

As marine scientists, we know that most bony fish have a gaseous swim bladder. As divers, we know that Boyle’s Law states the pressure and volume of a gas have an inverse relationship. The swim bladders in fish expand as they are brought to the surface due to the decrease in ambient pressure. Obviously this poses a huge health concern for the fish. Traditionally, scientists have used hypodermic needles to puncture the swim bladder to off-gas the fish as they come up from the dive. This is a very stressful process that often results in mortality. The ichthyologists and aquarists at Cal Academy have invented a solution to this problem, the fish decompression chamber.

After the fish are caught at 400 feet they are placed into a porous acrylic cylinder with a depth gauge. We then ascend to about 250 feet to slow our decompression accumulation while providing enough ambient pressure so the fish aren’t too stressed. The fish are then placed into a larger water filtration housing. Divers then puff a small bubble of nitrox gas into the lid before it is attached. As the team ascends, the bubble expands inside the filter and causes the chamber to hold a static pressure. Our team of aquarists meets us at 100 feet to attach an off board gas supply so the chamber does not lose pressure during the final ascent. Back on board the chase boat, the aquarists attach water filtration tubing and haul back to the aquaculture facility. They then spend two days constantly tending to the chambers to off gas the fish slowly and safely.

Our dives in Palau were incredible. Imagine the best aquarium you’ve ever seen and multiply it by ten! This attempts to describe Palau’s coral reefs. The diversity was not only remarkable, but overwhelming. At “West Past,” we couldn’t even lay a finger on the bottom at 200 feet because everything was exploding with life! Palau is also famous for becoming the first shark sanctuary in the world. Rightfully so, we saw sharks on almost every dive. During one of our collection dives off a vertical wall at 360 feet, we were surrounded by 20 reef sharks and one very curious 11 foot female tiger shark. It took every ounce of discipline to stay focused on the mission and not look up to say “wow!”

You might be wondering how we passed the time during these four to six hour dives. Frequently, we leisurely did video transects and documented the reefs with our cameras. Fish watching was a personal favorite. Time flew by studying a school of colorful Anthiadinae or a family of clownfish in their anemone. Other activities included: practicing line skills, studying the scientific names of local fish on laminated cards, cruising with the scooters, listening to music, spontaneous dance competitions, cutting away fishing line, and writing graduate school application essays. We also need to stay hydrated by drinking from our underwater hydration packs and keep up with our calories. Grapes, bananas, and tubular apple sauce are team favorites!

We did not return to the dive center until 4:00pm to 5:00pm or later. As tired as we were from our four hour dive, the work did not stop. The boat needed to be offloaded, gear rinsed, cylinders filled, and rebreathers disassembled and sanitized. We left the dive center at about 7:00pm to 7:30pm after our two hours of cleanup. By the time we got back to the hotel and took a quick shower, we walked to a nearby restaurant for dinner at 8:00pm to 8:30pm. Returning to our rooms at 10:00pm to 11:00pm, falling sleeping was not an issue. Then it at all started again the next day. This continued for four days straight, with one dry “day off,” then back at it for another four days.

I am extremely grateful to the California Academy of Sciences for allowing me the funding and privilege to accompany them on this expedition. The Palau expedition was a dream come true for the eight year old boy. The reef structure and diversity exceeded all expectations. Our deep team caught over 30 live specimens for the Steinhart Aquarium. It will be the first time that some of these species have ever been displayed in an aquarium. A few of these species are also new to science! Advancement in diving technologies has allowed us to explore these mesophotic ecosystems. Who knows what else we will discover on our next expedition to Easter Island!