Afraid to reproduce? Measuring fish reproduction in risky environments

George Jarvis, AAUS Master’s Scholar 2018

I spent the past two summers studying the reproductive behavior of bluebanded gobies, Lythrypnus dalli (Fig 1) at Santa Catalina Island, CA. Female gobies reproduce by laying nests of eggs, allowing direct examination of reproductive responses to environmental conditions. Bluebanded gobies are constantly threatened by a suite of natural predators, particularly kelp bass, Paralabrax clathratus (Fig 2), and gobies alter their behavior in response to this piscivore. My research aims to assess the short and long-term effects of risk on bluebanded goby reproduction through a series of caging experiments. This work has the potential to improve our understanding of how sublethal effects of predators, which are often overshadowed by lethal effects alone, may shape prey communities and behavior.

Fig. 1: A harem of bluebanded gobies in their natural reef environment (left) and a close-up of a male bluebanded goby (right, inset; photo credit: Maurice Roper).

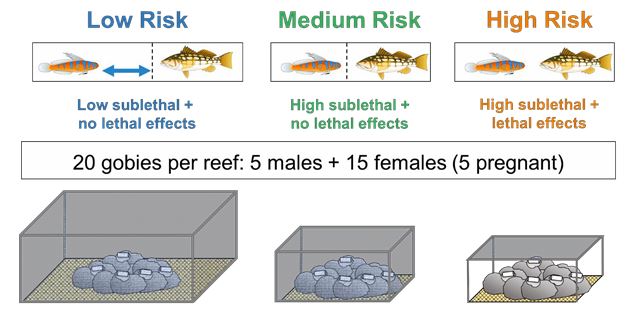

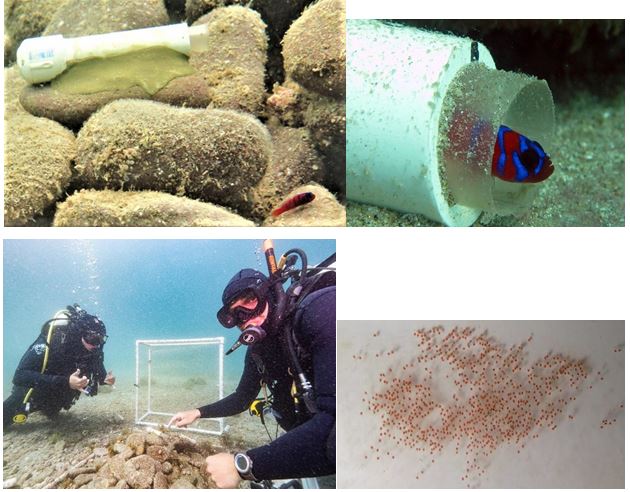

To test the effects of predators on reproduction in bluebanded gobies, I ran a manipulative experiment in Big Fisherman Cove, a marine reserve at USC’s Wrigley Marine Science Center (WMSC). I constructed a series of subtidal rocky reefs, stocked them with populations of 20 bluebanded gobies, and covered them with one of three cage types to simulate risk levels perceived by the gobies: large exclusion cages (low-risk environment), small exclusion cages (medium-risk environment), and small cages with side panels removed to allow for predators to move freely on and off the reefs (high-risk environment) (Fig.3). I also stocked each reef with artificial nests (short PVC tubed lined with acetate), where female gobies laid eggs to later be fertilized and guarded by males. I performed SCUBA surveys twice a week for one month, during which I checked each nest for eggs and photographed the nests when eggs were present. I uploaded those nest photos to my computer and counted the eggs to compare reproductive output among the three treatments.

Fig. 2: A kelp bass eyes a bluebanded goby on one of my experimental reefs.

Though analyses are ongoing, I’ve found that gobies lay the same number of eggs on each reef, regardless of risk level, and that this pattern persists over time. These results are consistent with our behavioral observations, where gobies exhibited similar risk response behaviors for exposure times and foraging rates, even when subjected to different risk levels. Interestingly, egg production varied over time, with maximum output mirroring the natural reproductive cycle for this species. These findings posit that predation risk is having less of an impact on prey populations than has been suggested in other marine systems, at least in this species of reef fish. As mentioned previously, this study was conducted in a marine reserve, where predators reach high, natural abundances not achieved in unprotected areas. As such, we may have seen a different result had this study taken place outside of the reserve, where predator presence, both lethal and sublethal, has been altered by anthropogenic activities.

Fig. 3: Schematic of the reefs and caging treatments. Blue shading on cages indicates mesh netting to exclude predators, and white cylinders

on each reef represent the artificial goby nests. Cartoons above show the physical separation between prey (gobies) and predators (kelp bass).

The AAUS scholarship has benefitted my thesis project immensely. Without this financial support, I would not have had the opportunity to gain invaluable field research, mentorship, and outreach experience at Catalina Island. Having the means to conduct research remotely allowed me to interact and foster professional relationships with top scientists and public stakeholders. I am grateful for AAUS and its continued support of graduate research. Thank you to all the fantastic volunteer divers and undergraduate researchers that have helped me carry out this project, and to my faculty mentors for their time and support during my thesis work. After my Master’s I hope to pursue more studies involving fitness responses and life history strategies of marine critters in a PhD program.

Fig. 4: Artificial nest and goby nearby (top left). Male guarding nest of eggs (top right; photo credit: Scott Hamilton). Me pointing to a nest with eggs

present, and dive buddy, Hunter, throwing up double shakas in elation (bottom left; photo credit: Maurice Roper). A typical goby nest photographed

underwater; each red dot is a single fertilized egg (bottom right).

Lastly, if you are an undergraduate or graduate student interested in conducting field research at WMSC, check out their fellowship opportunities at this link: https://dornsife.usc.edu/wrigley/wrigleysummerfellowship/